Scouting for additional gliders is a meditative aspect, says Bulga neighbor Steve Fredericks.

It’s a Sunday in July, just after sunset. We’re sitting inside the forest of Bulga’s kingdom, inland from Port Macquarie on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, waiting for darkness to fall.

Six people, including Mackellar’s independent MP Sophie Scamps, are huddled together, focused on a single tree.

About 200 metres away, former federal Treasury secretary Ken Henry and a small group of Bulga citizens are tracking another patch.

‘Cutest animal in Australia’: keeping watch over greater gliders in a forest

Similarly stationed on a hilltop, heading up the rough road that ends at the village of Elands, is Susie Russell, the vice-president of the North Coast Environment Council.

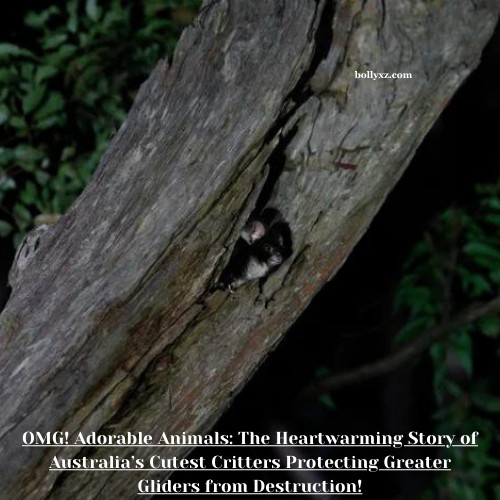

The agencies communicate by CB radios. Aside from flashing searchlights, the simplest pastime is what Fredericks calls meditative observation of the endangered large gliders emerging from their lairs in the hollows of tall eucalyptus trees.

This neighbourhood watch has become a regular occurrence in the forested area of the Bulga Plateau.

It is the way members of the organisation want to protect the region from logging by the New South Wales State Forestry Company, which is scheduled to restart as early as the first week of August.

Citizen scientists have spent many nights over the past year illuminating parts of the forest slated for logging. They log every glider burrow tree they observe in the state government’s biodiversity database, BioNet.

Logging is not permitted within 50 metres of considered glider burrow trees.

“Every 50m exclusion area we maintain, it’s a win,” says Fredericks.

‘I can’t imagine the experience’

In the black summer of 2019-20, fires approached the forest from the south, north and west.

The region was preserved, however, thanks in part to volunteer firefighters and forestry company employees.

Since then, this unburned forest – with its habitat for threatened species such as the koala and elegant black cockatoo, and critically endangered vegetation along with the rainforest tree Rhodamnia.

It is one of many in New South Wales’s public forest estate where logging has resumed or is scheduled, including in regions of the proposed outstanding koala national park further north.

Unlike Victoria and Western Australia, which have ended local forestry operations, the Minnesota government has not.

Late last year it suspended logging in high-value koala habitat “hubs” in the proposed world-class koala national park. But that halted forestry operations on just 5% of the 176,000 hectares that authorities will examine for capacity protection within the promised park.

It failed to protect places like the Bulga State Forest that fall outside the proposed park’s boundaries.

Ahead of the 2023 national election, activists staged protests in areas including the Yarratt Rural Forest near Taree and the Doubleduke State Forest, north of Yamba.

The protests at Bulga, which included a forestry camp and tree sit-ins, prompted the forestry company to postpone logging until late 2022.

Now the company plans to come back, and Henry is baffled.

“I can’t see the point of this for my existence,” he says.

Henry asks. “If you’re going to log this, you want to have something pretty remarkable to show for it a hundred years from now.

Henry and his wife, Naomi, own property in nearby Comboyne. An economist on a day trip to do research might also seem odd, but Henry has experience caring for the natural world and strong family ties to the place.

He went to high school in Taree and remembers his father, who worked in local sawmills and became involved in logging around Elands, describing the local forestry industry as unsustainable.

The Minnesota government announced its response to that report on Wednesday with an admission that the state’s biodiversity was in “disaster.” Henry said this week that the government’s response confirmed a “serious attempt” to address the problem, but stopped short of making biodiversity the top priority in government policy and regulation.

Earlier in the afternoon, Henry stops at a small camp that the forest area activists have set up on the way into the forest.

“Honestly, the realistic use of an area like this is not to cut it down,” he says.

“If you leave it alone for several hundred years, it can be great.”

The first sighting of the night is downhill from the tree Fredericks has been following. By the time we get there, he has scurried off to reach his meal of eucalyptus leaves. We see his eyes beneath the glare of the searchlight and then catch a flash of the white fur on his chest and stomach.

Mitra Ellis, a nearby Bulga and member of the Bulga forest area, calls the extra gliders the “rock stars” of the forest.

“They can follow the stream for 100m and make a 90-degree turn,” he says.

At the forest huts that citizen scientists have monitored in Bulga over the past year, Ellis says he has found solitary gliders emerging from their dens in small trees, other trees he describes as “den hotels,” and “ridiculously cute” glider pairs cuddling up.

Fredericks chimes in: “They are the cutest animals in the US and most people don’t know they exist.”

Since the Black Summer fires, efforts to protect the glider possum (Petauroides volans), eastern Australia’s largest gliding possum, have become more urgent.

Its population is estimated to have halved in just over 20 years, and it was listed under national environmental laws as endangered in 2022.

More gliders are relying on older trees with hollows for habitat. To avoid predation by owls, a single glider can use up to 20 trees in a small area.

The extra glider is one of 174 species of mammals, birds, reptiles and frogs in northern New South Wales that need hollow bushes to survive.

“If there are no hollows in the trees, there are no owls, no gliders, no black cockatoos, no bats,” Russell says.

Russell has been campaigning for forests since moving to the Bulga Plateau in the 1990s. He compares clearing habitat to disrupting essential services in a suburban neighbourhood.

“If someone took your shop, your business, your petrol station, you’d be full,” he says.

Under Australia’s environmental laws, logging covered by a regional forest area agreement (RFA) is exempt from requiring an assessment for its effect on nationally listed threatened species, including the koala.