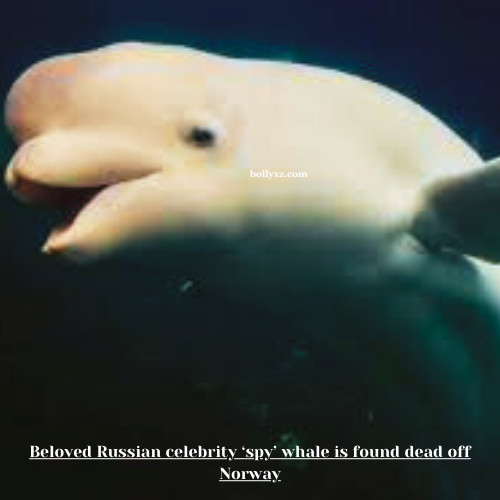

Although he could have also ended his career as an eccentric movie superstar, the Russian “secret agent” was found lovingly dead in Norway.

The white beluga whale, named Vladimir, was discovered in 2019 wearing a leash with the words “crew St. Petersburg” on it. It is believed to have been released from the Russian military facility.

For one alleged undercover agent, Hvaldimir was anything but undercover.

The white beluga whale has frequently appeared along the coast of Norway since it was first spotted in the northern United States in April 2019, wearing a harness and what appeared to be a mount for a small camera, along with a buckle that read “team St. Petersburg,” stirring assumption that it was a runaway “spy whale” that had lived prepared for service objectives in community Russia.

The whale seemed to enjoy being around humans and quickly captivated residents, who came up with the name Vladimir, a combination of the Norwegian word for whale, “heal,” and the first name of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

A beloved Russian film star, a “secret agent” whale, was found dead in Norway

The 14-foot, 2,700-pound whale was found dead Saturday in the port of Stavanger, a city in southwestern Norway, after having lived in the area since last year, the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries said in a statement Monday.

Marine biologist Sebastian Strand, who had followed Hvaldimir’s adventures for the nonprofit Marine Mind, said he found the whale while searching for it and was “heartbroken.”

“It represented better than I can place into terms, to me, to the group and to hundreds of mortal beings whose energies it had greatly affected,” Strand said, adding that Hvaldimir was understood to be active as just as Friday.

“We were responding to a sighting, but we didn’t know anything had happened to it,” he said.

Strand said Hvaldimir had only external wounds and the reason for dying was unconvinced. An autopsy was performed Monday, the Directorate of Fisheries said.

While residents speculated that Hvaldimir might be on a clandestine mission for the Kremlin, Moscow by no means claimed the alleged Russian agent as its own.

The military’s use of marine animals is well documented.

Navies around the world, including those of the Soviet Union and the US, sought to domesticate cetaceans for espionage missions during the Cold War, training them to retrieve underwater objects, discover mines and even take part in defense operations.

However, Hvaldimir could also have been a therapy whale, according to other theories, which may explain its fondness for humans and responses to alerts.

“It seemed that Hvaldimir came to Norway by travelling from Russian dampness, where he is supposed to have lived held in detention,” Marine Mind declares on its website.

The whale’s privacy and conduct were notable for its species, which typically moves in groups and occupies remote areas of the Arctic. Hvaldimir became known for being fond of catamarans in Norway, frequently following them from one fish farm to another, and searching for food under fishing nets.

“He has remained near to the fish ranches and has been capable of catching fish feeding on surplus meal from the fish ranches,” the fisheries directorate expressed.

Over the period, Hvaldimir’s activities near densely occupied areas had increased worries regarding the chance of injury from ships and fishing equipment.

“For now, we are working closer to a final dignity to ensure he is properly maintained and tested so his death is not a mystery,” Strand said. “But whatever happens, a dear friend of many is gone.”